Our History

NBSS was founded in 1881 as North Bennet Street Industrial School. Our founding mission was to enable immigrants to adjust to their new country by learning the skills needed for gainful employment.

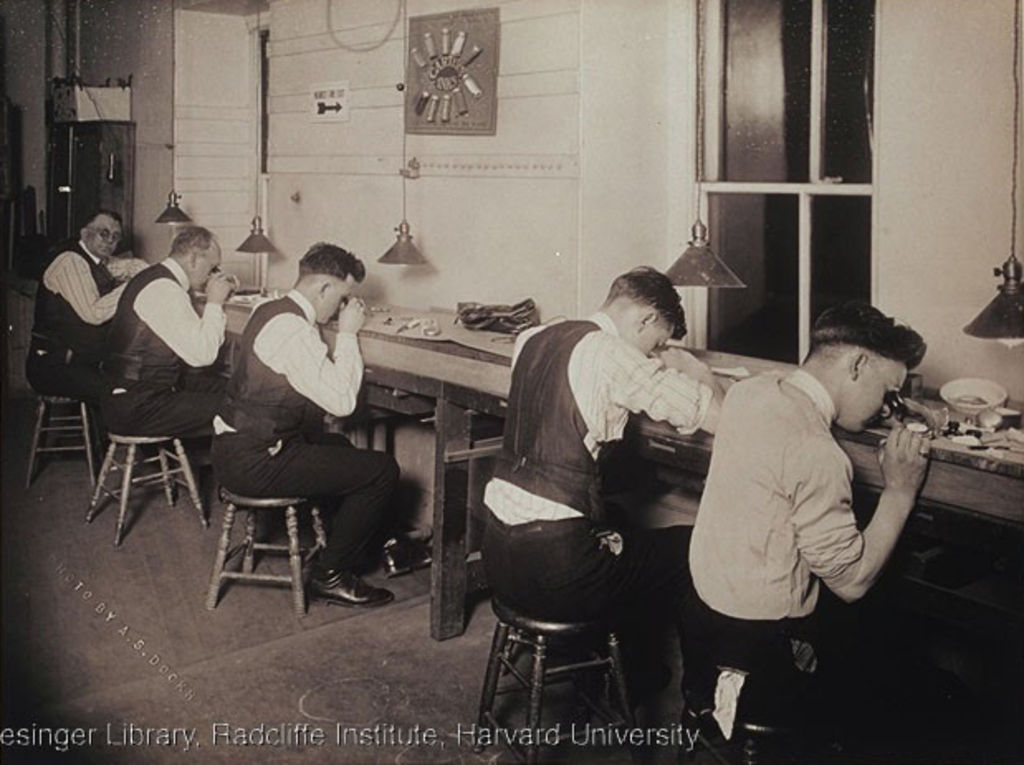

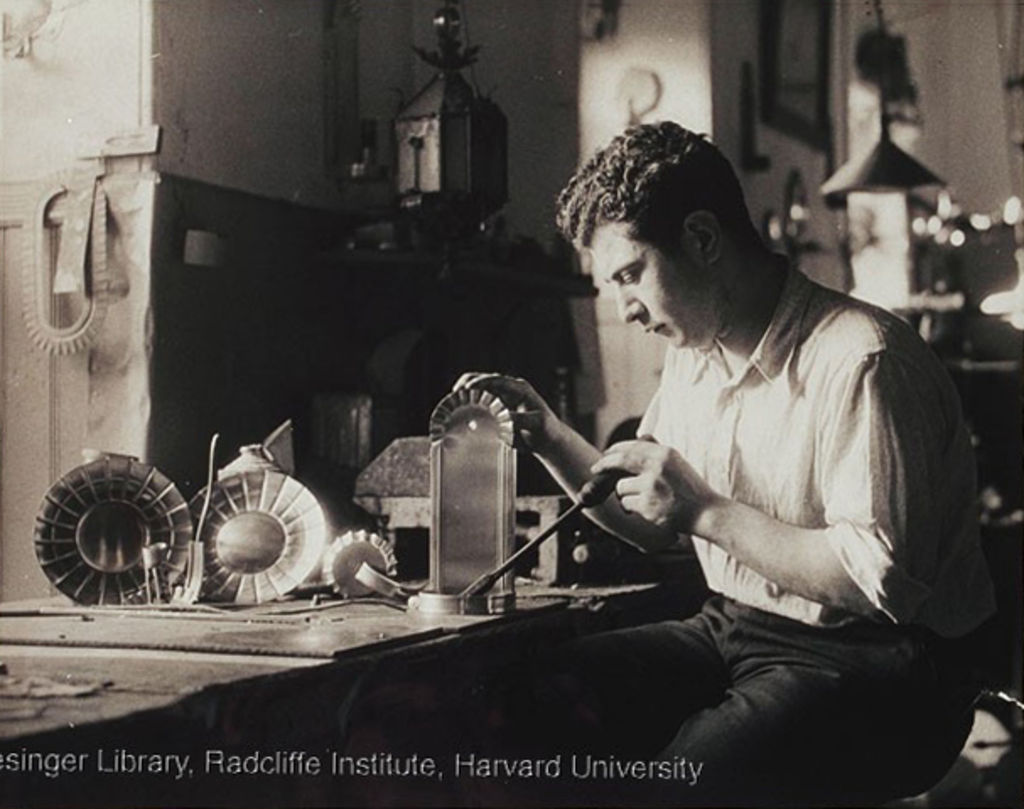

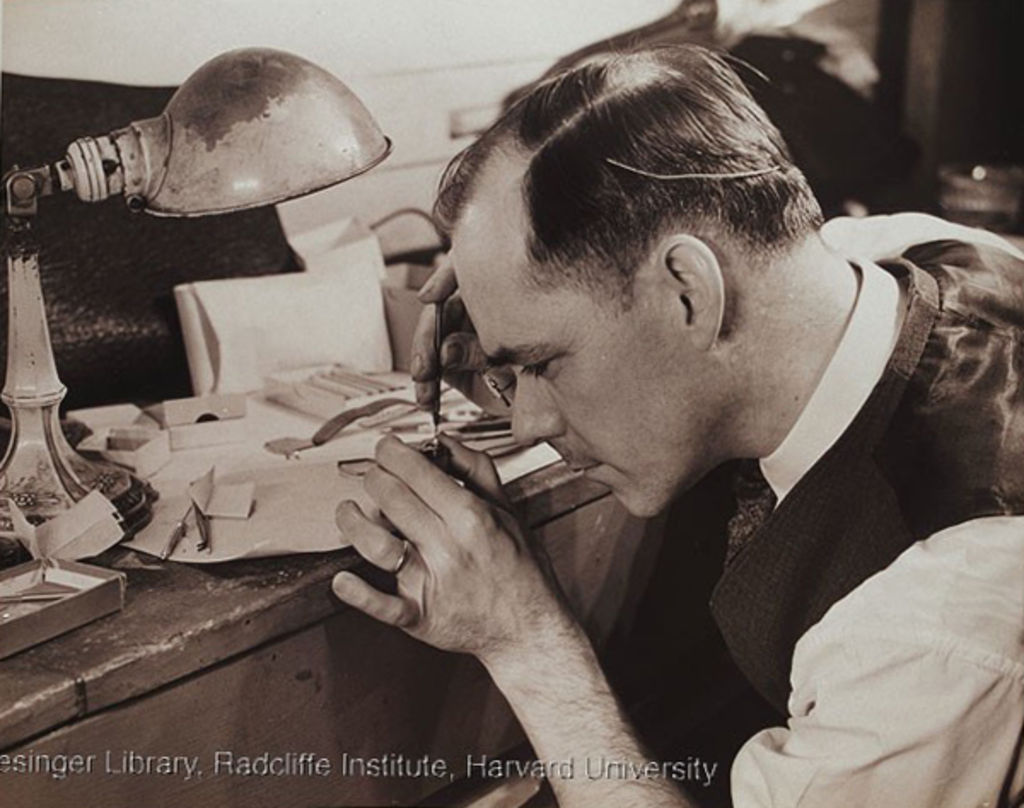

In the past, we’ve offered a variety of vocational training courses, such as pottery, printing, sewing, sheet metal work, and watch repair. Though our programs may have changed, we retain our core commitment to train individuals for employment using time-honored methods and skills. To learn more, view our timeline below, and check out the book Rewarding Work: A History of Boston’s North Bennet Street School.

Since its founding, NBSS has contributed to the character of Boston as a city that cares about its neighborhoods, the education of its citizens, and the vibrancy of its culture. Through various social services, like childhood education, recreational activities, and pre-vocational and trade training, we’ve helped generations of Boston’s immigrants make productive lives in their new homeland.

Timeline

1880s

In 1881, the Associated Charities Volunteers establishes the North End Industrial Home to serve immigrants in the North End. Early programs taught women skills for employment, paid them for piecework and provided social services.

Founding visionary Pauline Agassiz Shaw furthers the mission of the institution, developing and funding dozens of kindergarten classes and Boston’s first day nurseries.

By 1885, the Board of Managers formally incorporates and renames the institution the North Bennet Street Industrial School (NBSIS). Shaw becoming President of the Board and serves until 1915.

Though the School raises enough funds to purchase the building, a disastrous fire nearly halts their efforts at social and educational reform. NBSIS rebuilds.

1890s

Parallel and mutually reinforcing manual skills training and social service departments emerge. Among these, in response to neighborhood children not attending school or finishing school, NBSIS contracts with the Boston Public School system to provide manual training classes for 300 young students.

Recreational programming for students young and old soon follows, including libraries, reading rooms, and a gymnasium.

NBSIS adopts the Swedish Sloyd system of instruction, which proves so popular that a Sloyd School for Teacher Training is established at NBSIS. It continues to grow for over two decades before outgrows its third-floor space and moves off-site.

1900s

By the early 1900s, the rising rate of immigration caused the School to create more systematic ways of helping newcomers settle in America. Its role as a settlement house and the hiring of Zelda Brown as head resident formalized the social service role, creating a social service house and much-needed efficiencies.

The Board hired Alvin E. Dodd, the first trained administrator to lead NBSS. To better serve the community and maintain both the manual training and social service programs, Dodd divided the School into departments, established after-work programs, and expanded the services provided by Social Service House including a Savings Society and offices for the local probation officer, the Animal Rescue League, and an on-site physician.

1910s

The School formalized vocational training classes and started English classes for immigrants. By 1911, 28 salaried teachers and 55 volunteers served more than 1,100 students in a growing neighborhood of 35,000 individuals.

School clubs and affiliated groups exploded at NBSIS during this time, numbering over three dozen in all. Some included the City History Club, Italian Red Cross, Saturday Evening Girls Club, North End Union, and the Legal Aid Bureau.

In 1915, George Greener, formerly the School’s ceramics instructor, becomes its Director. Caddy Camps are established to enable inner city boys to spend the summer working in the country where they earned tips, benefited from the fresh air and exercise and learned from the golfers, many of whom were professional lawyers, doctors, and businessmen. The camps run until 1983.

Pauline Agassiz Shaw, the visionary educator, social reformer, philanthropist, and founder of NBSS, passes away in 1917. Thousands attend her funeral at Faneuil Hall, which features notable speakers including the Governor of Massachusetts.

During this decade, the great Molasses Flood, World War I, and the 1918-19 flu pandemic all occur. NBSIS carries on.

1920s

Greener begins dual programs—handmade craft (homespun) and power machine operators—traditional crafts and skills for jobs. Post WWI, Greener introduces programs for veterans including Watch Repair, Cabinet Making, House Framing, Printing, and Jewelry Engraving.

Social service programs developed in this decade include the Vocational Guidance and Placement Bureau, and the Play School for Habit Training. Several allied retail shops also presented opportunities to expand the footprint and funding of NBSIS.

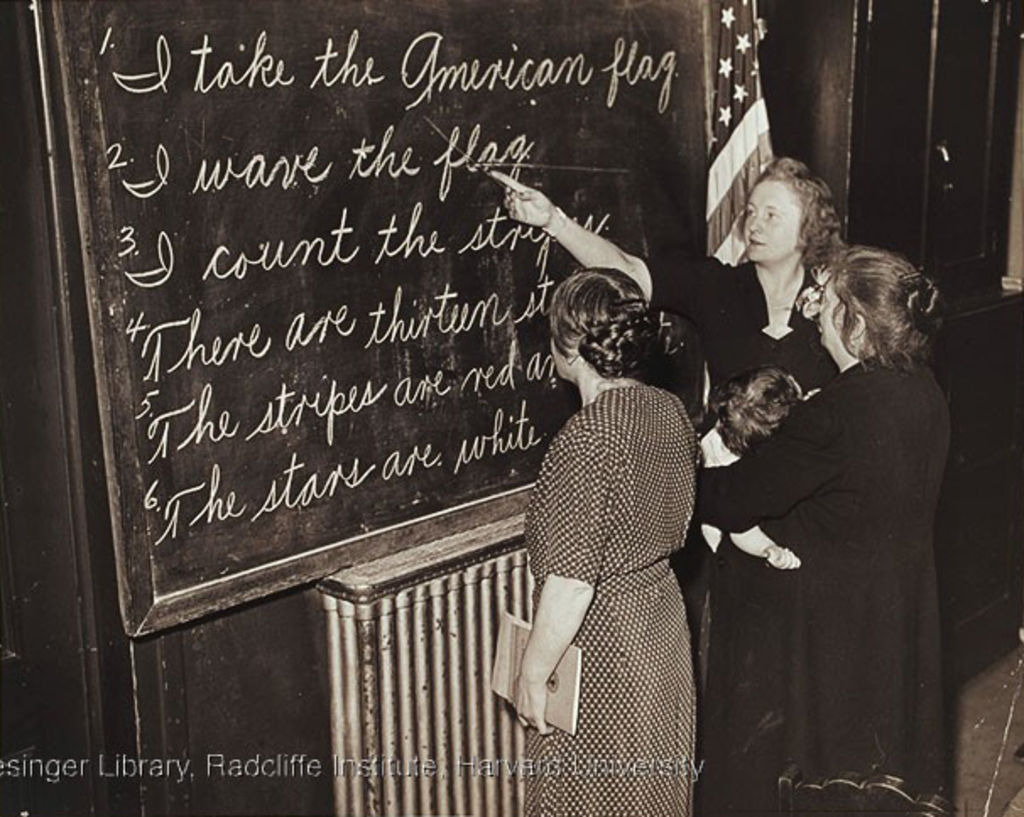

NBSIS supports immigrants with classes in English language, naturalization, civics. Summer youth camps grow in size.

1930s

The School establishes a Credit Union and Work Relief Program, addressing both local needs and broader issues in society. Supporting citizens through the Great Depression, NBSIS adds vocational training in Clay Modeling, Lighting Fixture Industry, Power Machine Operation, Watch Repair, Accounting & Bookkeeping, and Poster/Window Card Design, among others.

1940s

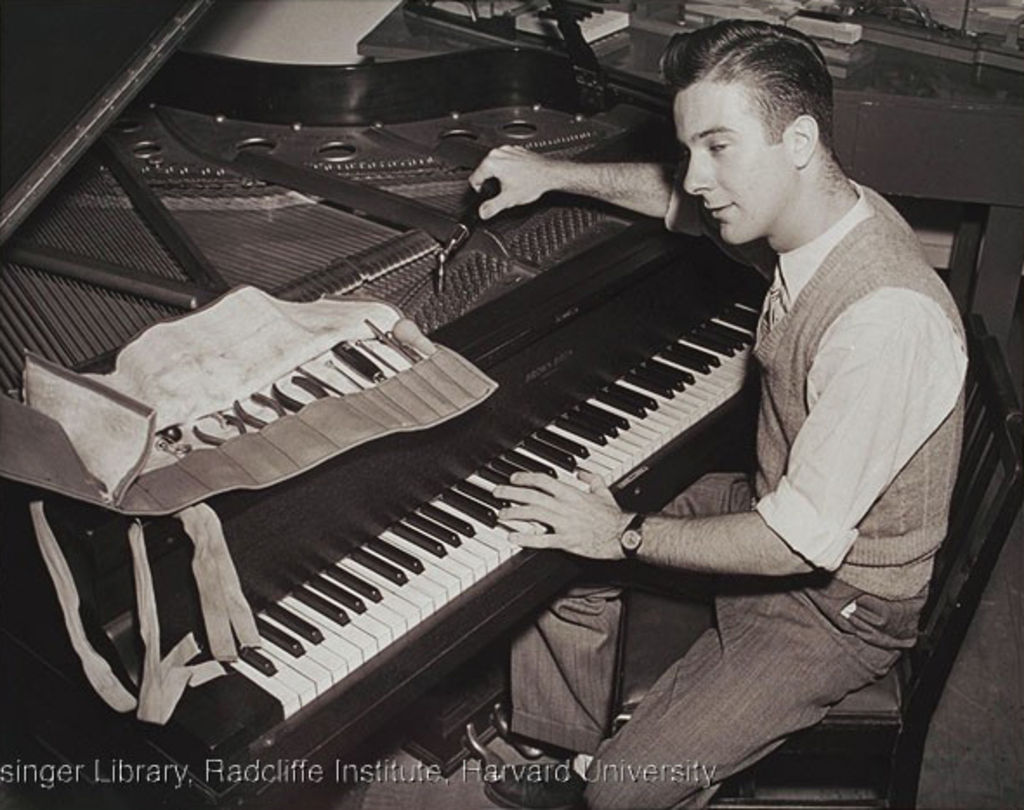

Veterans returning from WWII enroll at NBSIS on the G.I. Bill, providing them with civilian careers that leverage their skills. Training programs expand, many of which continue to be offered by the School today: Cabinet & Furniture Making, Jewelry Making & Engraving, Carpentry, and Piano Technology.

1950s

The elevated Central Artery effectively cuts off the North End neighborhood from the rest of Boston. The School continues to grow its scope and reach, with more students coming from outside of the City via nearby North Station.

1960s

The School continues to support the local community and experiments with offerings for restless North End youth, including after-school programs, sport activities, and recreational classes.

The Social Service House becomes the George C. Greener Memorial Building in 1964, housing its nursery school.

1970s

Continuing its focus on career education, NBSIS transfers some social services to other entities, and launches new programs in Locksmithing & Security Technology and Advanced Piano Technology.

1980s

NBSS celebrates its 100th anniversary.

After a years-long process, accreditation by National Association of Trade & Technical Schools is approved in 1983. “Industrial” dropped from the School name as it looks to focus on traditional crafts and trades. In keeping with this, the School sunsets its classes in Camera Repair, Offset Printing, and Watch & Clock Repair, among others. The last of the School’s social service programs move to the North End Union during this time.

Growing its capacity, NBSS launches new programs in Violin Making & Repair (1983), Bookbinding (1986), and Preservation Carpentry (1986).

1990s

The School’s day care operations move to the North End Union. Tim Williams retires in 1992, and Cindy Stone is hired as the new Executive Director. A School-wide Improvement Plan lays the groundwork for growth and adaptation to changing industries.

The School launches the first of its Workshops (now Community Education classes) to “promote continuing development of the skills and knowledge of artisans, both professional and amateur, in their respective fields.” These short, project-based courses originally develop out of curricula from the School’s full-time programs.

2000s

Due to enrollment growth and limited building capacity, the School’s Carpentry and Preservation Carpentry programs move to auxiliary facilities in Arlington.

Cindy Stone resigns in 2005, and Walter McDonald is appointed Acting Director. In 2006, architect and NBSS graduate Miguel Gómez Ibáñez CF ’99 is hired as President.

2010s

A pilot program for manual skills training for John Eliot School middle-school students is established in 2010. Similarly, a partnership with Boston Public Schools to tune/repair pianos begins. By 2016, Partnerships begin with Boston’s Madison Park Technical Vocational High School, the Donald McKay K-8 School, and Dorchester Youth Collaborative.

Lacking space in its original building, in 2011 the Locksmithing & Security Technology program moves offsite. Within two years, NBSS launches and concludes its search for a new home, raising over $14M in funds and purchasing two city buildings in the North End. By September 2013—after an intense year of activity—the School and all nine of its programs move under one roof at 150 North Street.

In 2015, the Lives & Livelihoods Campaign begins with goal of raising $20M for the School’s scholarships and endowment. By December 2018, NBSS would conclude the campaign a year early, having exceeded its already ambitious goal.

In 2018, Miguel Gómez Ibáñez CF ’99 retires from his role as President. Artist and educator Sarah Turner is hired as the next leader of the School in 2019.

The Mayor’s Office of Workforce Development awards NBSS a Neighborhood Jobs Trust grant, and the School also receives a Workforce Skills Cabinet grant from the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. NBSS receives Massachusetts Cultural Facilities grant every year from 2015 to the end of the decade.

2020s

In March 2020, the School temporarily closes its doors to ensure the health and safety of its community in light of the Covid-19 pandemic, and reopens again in September 2020. The School’s faculty, staff, and students react with speed and aplomb, moving to remote work and training to ensure continued operations. Donors, Board members, alumni, and friends lend their support, guidance, and expertise to new initiatives. The School perseveres.

It was a testament to the NBSS community’s ability to flex, adapt, and experiment—and indeed, this was just the most recent moment in a long history of nimbleness for an institution that began as a collection of neighborhood social services in Boston’s North End in 1881.

NBSS celebrated its 140th anniversary in 2021, looking forward to another century and more of growth and progress.

Images courtesy Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University