Restoring a Relic from Boston’s Industrial Past

During my time in the Cabinet & Furniture Making program at NBSS, we were required to learn machine maintenance and shop care, alongside our training as cabinet and furniture makers.

Having a mechanical background, I was drawn to this aspect of my education, and have since made it a regular part of my career as a woodworker. (Case in point, a large part of my role as the Shop Technician for the School’s Continuing Education Department is to maintain and restore the machinery in the program.) With the skills I developed at NBSS, I have been able to restore and maintain a range of vintage machinery—both in my shop in Charlestown, as well as working for clients around New England.

As far back as I can remember, I’ve been interested in mechanisms and mechanical devices, in particular older and antique machinery. Before my time as a student at NBSS, I was the house mechanic at a vintage bowling alley, which opened in the 1950’s and was still using its original pin-setters. They were intricate, amazing pieces of equipment. Though I was trained to maintain very specific machines like those, I’ve since realized that there are only so many ways for a machine to fit together. Whether a vintage pinsetter or modern woodworking equipment, the principles behind them are largely similar.

In 2016, my friend and fellow machine enthusiast Tim invited me over to his shop with the tease of having “something interesting” he bought on Craigslist that I’d like to see. When I arrived, he directed me to an object covered in a plastic sheet on his porch. Underneath was a simply superb, small-scale bandsaw—old, iron, and beautiful. It had “Boston MA” cast into the frame of the saw and was made by the J.M. Marston Company of Boston. Though we parted ways after lunch that day (talking much about the 24″ bandsaw made just miles away from my own shop), Tim called me a couple weeks later to see if I’d be interested in buying it. While I had no real plan for the machine other than to admire it, I agreed right away.

After researching more about its history however, it seemed appropriate that, having been rescued from the scrap heap, and returned home to Boston, the 24″ bandsaw should be restored. So began my journey into restoring this antique machine.

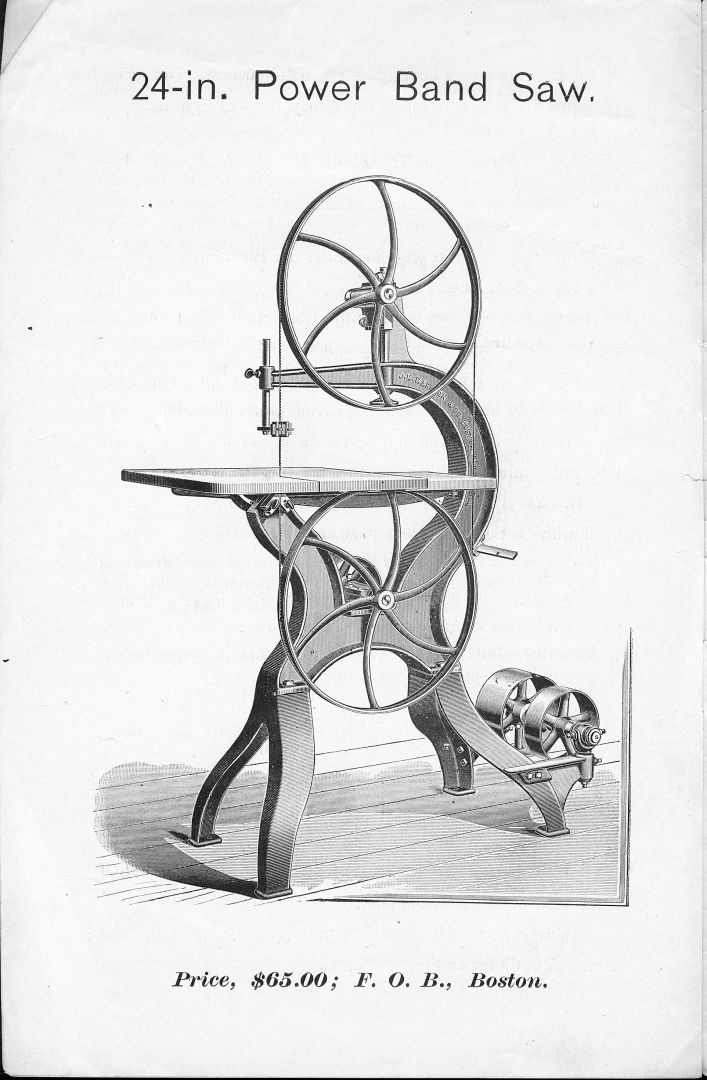

The J.M. Marston Co. was a maker of cast iron machinery for the growing industrial trades in Boston. Among the machinery built by the company was a line of early bandsaws—some foot-powered, and others powered from an overhead line shaft. These machines were intended to be a new type of saw, smaller and more portable than the massive saws being produced by other firms. The original advertising from J.M. Marston indicates that they intended to market these new smaller saws to smaller shops that had neither the space nor the budget for a larger machine. In the early days of industrialized woodworking, a small bandsaw would be able to save hours and hours of handwork that would otherwise slow production.

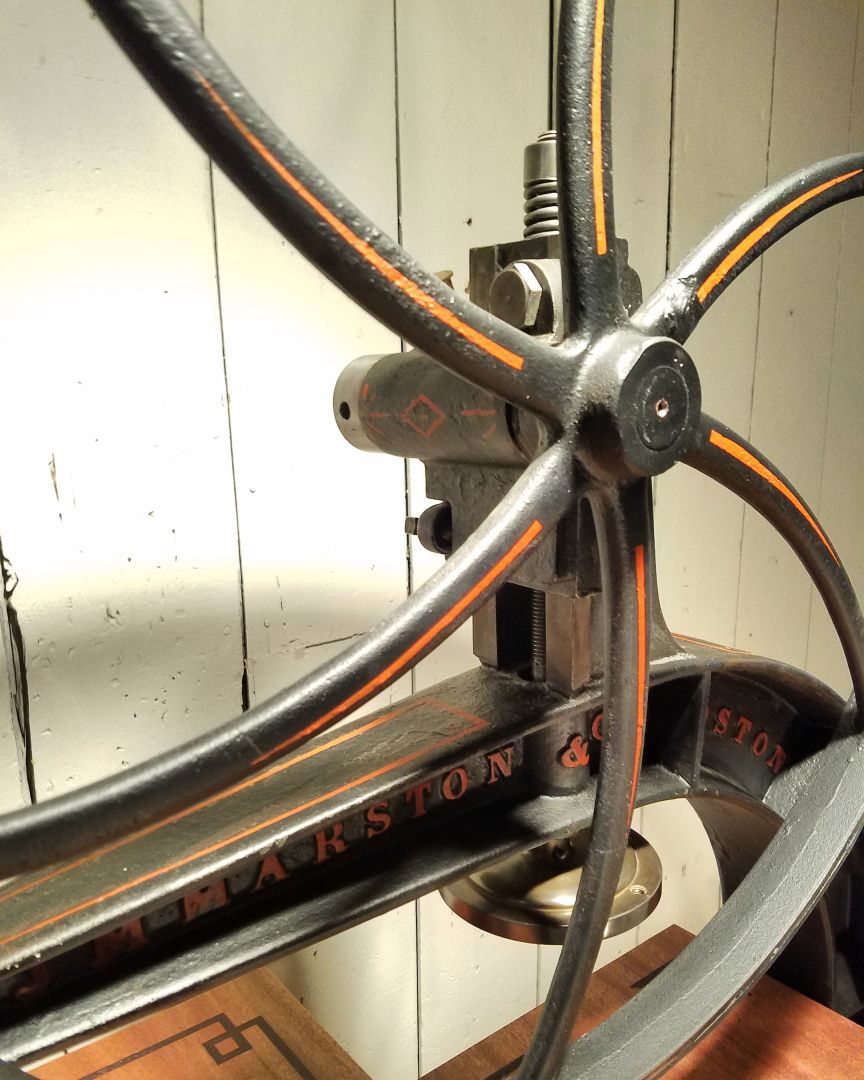

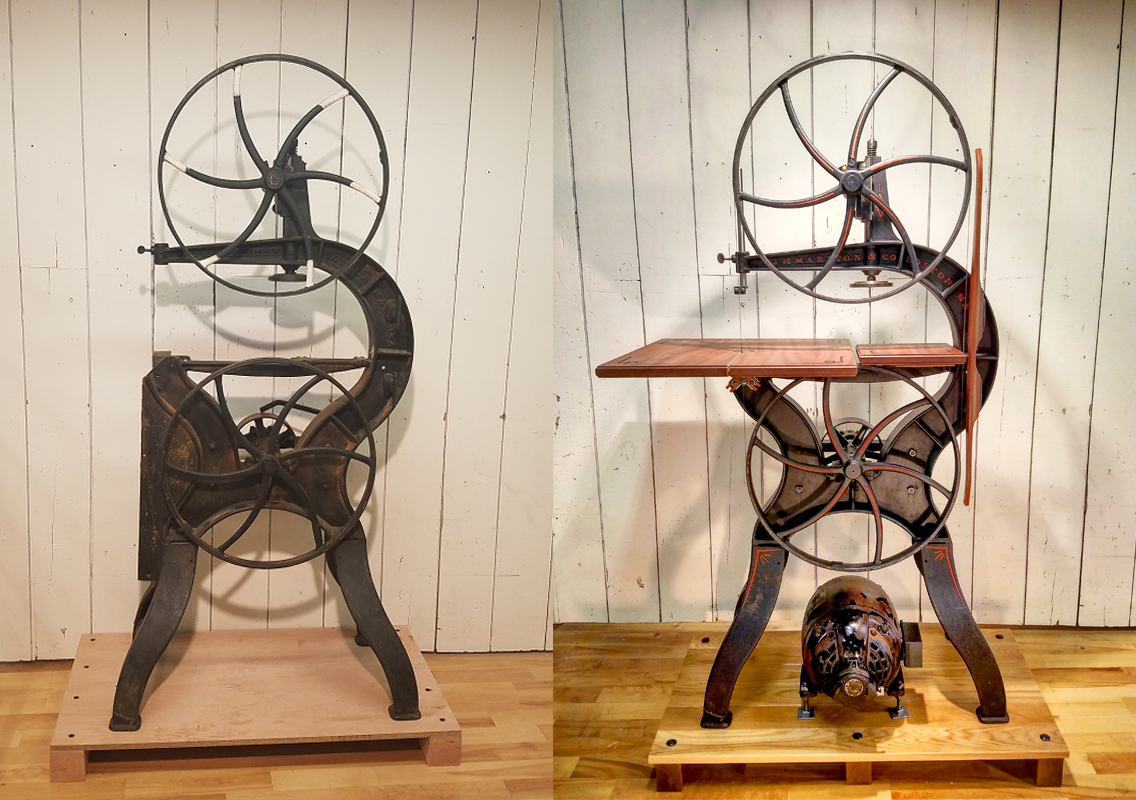

The machine had clearly been neglected for a long time, and had a hard life. The first step – as in any restoration project – was simply cleaning, to access the state of the surface under the years of accumulated grease and grime. Surprisingly, the majority of the original black paint on the body, and even some pin striping of the saw had survived. The lower portion of the saw and its legs would definitely need paint, however.

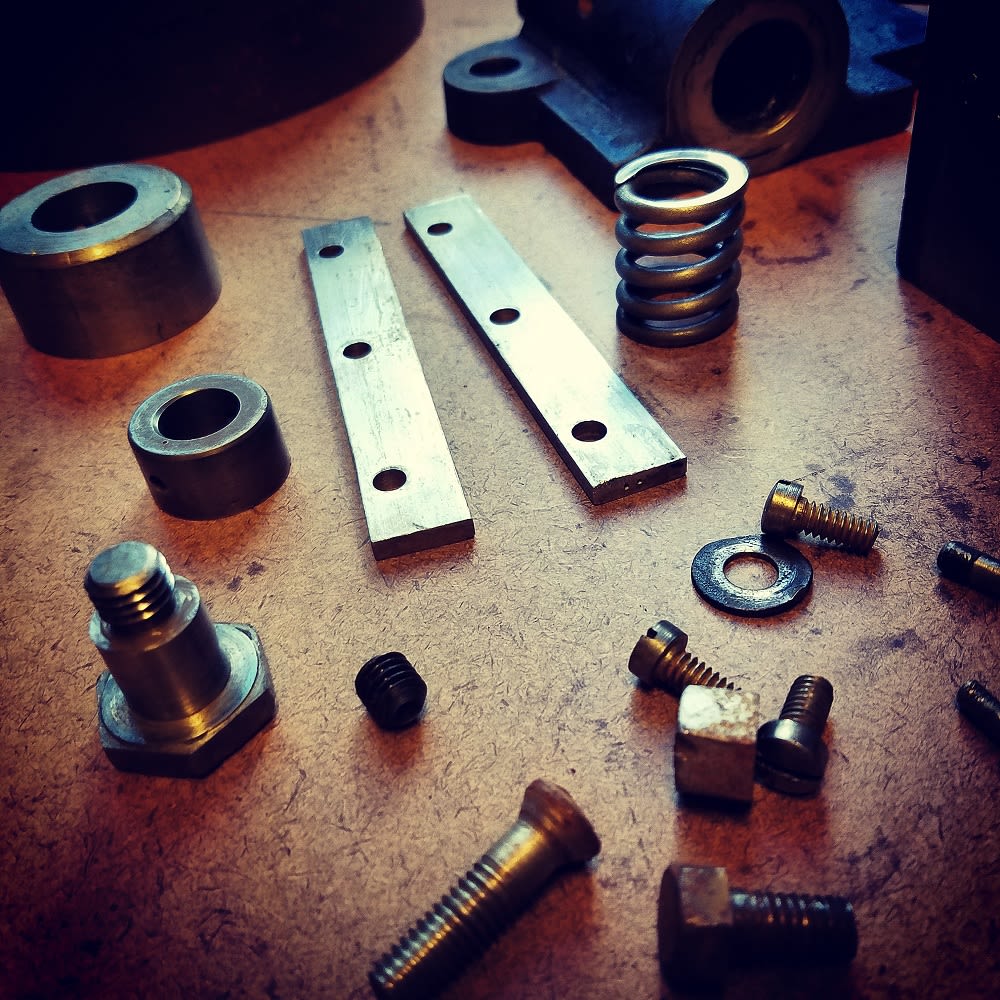

Next up: inventory and assessment. The vintage bandsaw was missing its guides, tires, motor, countershaft, and critically both its wooden table and cast iron table mounting trunnion. These items were the most glaring and pressing needs for restoration. True to my craft, I made short work of the wooden table, but the cast iron trunnion – which required making a pattern in wood – proved another matter altogether. Though a steep learning curve (it’s a woodworking skill all its own), I was eventually able to successfully produce the required piece, and off to the foundry it went.

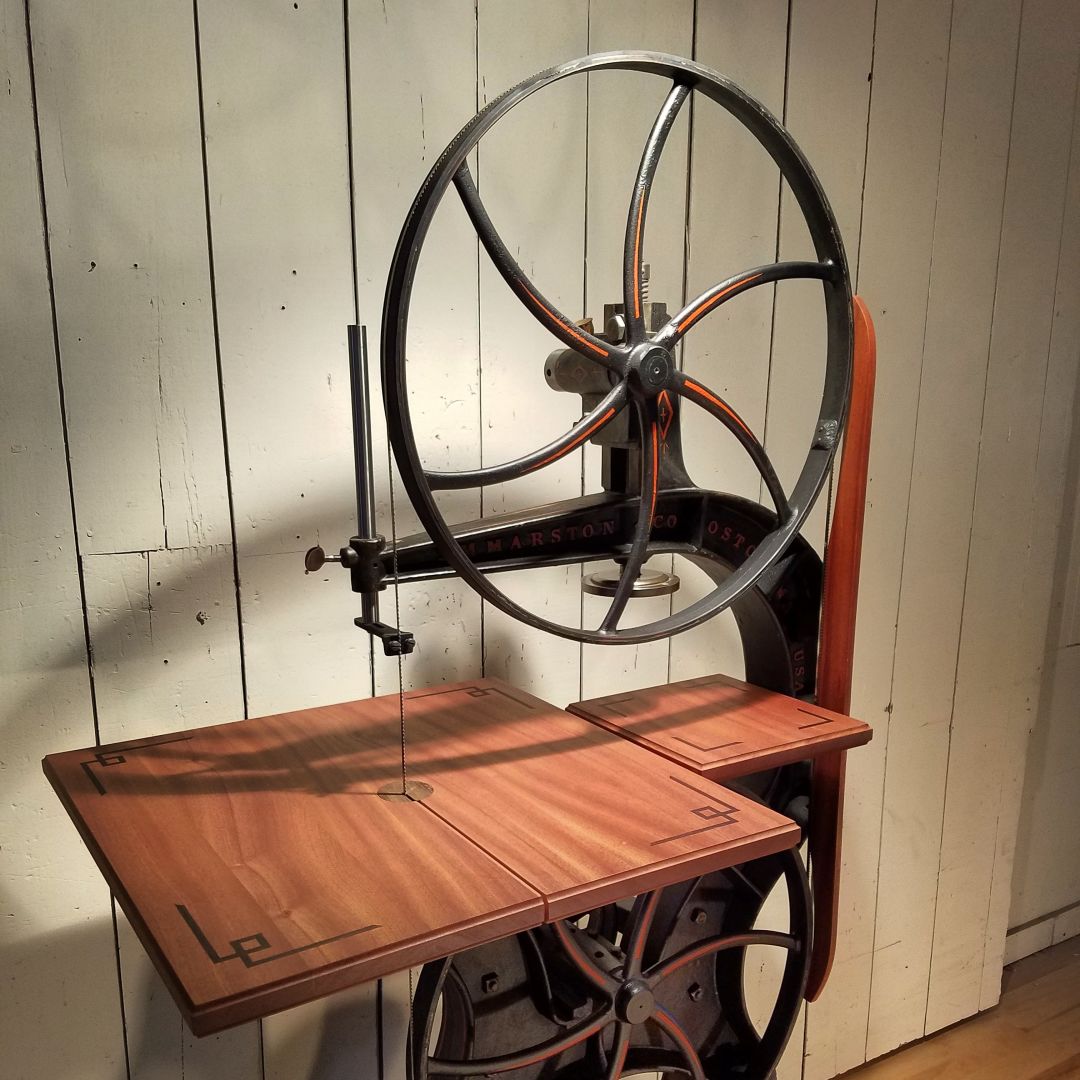

Once the pattern had been cast in iron I machined it to fit the original mount on the saw. Fortunately for me the parts on this saw had clearly been designed to be simple to build, and as a result is simple to reproduce. Next, I turned my attention to the table. The original would have been wood, and though the 1893 Marston brochure (pdf, see page 7) lists the table as “kiln dried hardwood,” it doesn’t name the species. I decided to spend a little extra time and energy to embellish the table in the decorative theme of the late 19th century, and chose sapele, with a wenge inlay. (Note to NBSS grads: the inlay is a particular pattern you should recognize, as I took my inspiration from the Shaker nightstand project.)

Now by this point I had been avoiding painting the machine for quite some time, debating between myself to preserve the original surface or repaint everything. My inner conservator won out, and I chose to repaint the legs, where the paint had been badly damaged, as well as paint my new reproduction parts. To keep these repainted parts from looking too new against the original surface on the body of the machine, I then top coated the entire surface with a flat lacquer to seal, stabilize and protect the original paint without adding any sheen, and to harmonize the sheen and color across both the new and preserved original surfaces. From there I went onto reestablishing the pin striping that would have been on the machine when it arrived in its first shop. Taking the cue from my original assessment, I selected a red-orange color to match the original pinstripe, and after consulting some reference material of the time period, I went with a design that would have been appropriate to the era. I followed the edict “more is definitely more” when it came to the motif.

The final step was re-assembly. As any restorer understands, having become so well acquainted with the piece throughout the process, I was able to move quickly and assemble the saw without trouble. Though it now looks superb and works beautifully, I know that this will never be my main bandsaw in the shop—it has neither the power or capacity needed to handle everyday work. Still, it will always have a place with me, just like the memories of the restoration itself, and the skills I learned in the process (research, pattern making, metal working, and even hunting vintage iron).

Having found and restored the J.M. Marston bandsaw, I’ve since developed a taste for Massachusetts-made machinery, particularly those from Boston. So far I have also found a lathe from the American Tool & Machine Company—with Boston cast into it, just like the bandsaw. My hope is that eventually I will be able to furnish a shop entirely with 19th century Boston-made machinery. It’s a lofty goal, and potentially impossible, but the search and process of restoring antique machinery is more than half the fun.