Founder’s Day, Part II: Sloyd & Training The Whole Person

Born on February 6, 1841, Pauline Agassiz Shaw was a philanthropist, educator, and social reformer who significantly impacted not only our School community, but also the history of Boston and the nation. We’ll celebrate our annual Founder’s Day on February 5, 2026, and invite all those in our extended community to participate in a celebration of Pauline’s life and legacy—and our entire community.

Below is a summary of the origins of the Sloyd educational model at North Bennet Street Industrial School, originally printed in our 2008 Benchmarks magazine.

From the beginning, North Bennet Street Industrial School was a pioneer in advocating the value of hand skills training to society. The manual arts training movement known in Sweden as Educational Sloyd (slojd means ‘craft’ or ‘manual skill’) was brought to this country in large part through the efforts of the school’s founder, Pauline Agassiz Shaw.

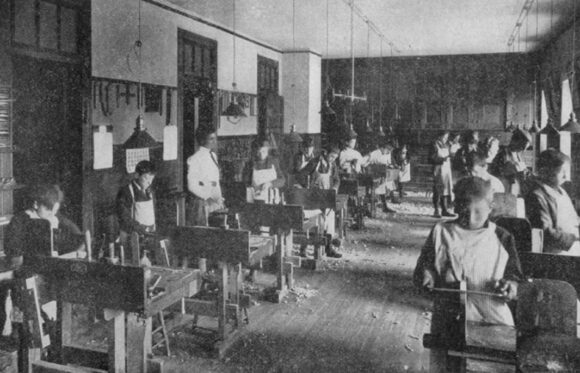

With North Bennet Street Industrial School established in the early 1880’s, Pauline set to work on expanding the vocational training curriculum. In 1889, she hired Gustaf Larsson from the Sloyd School in Naas, Sweden, to come to North Bennet Street Industrial School to develop a similar prototype in suitable for students in Boston. Met with great success, the effort expanded two years later when an entire floor of the School was converted to a training program for Sloyd teachers headed by Larsson.

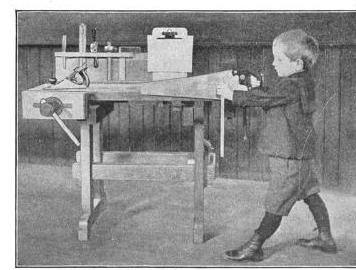

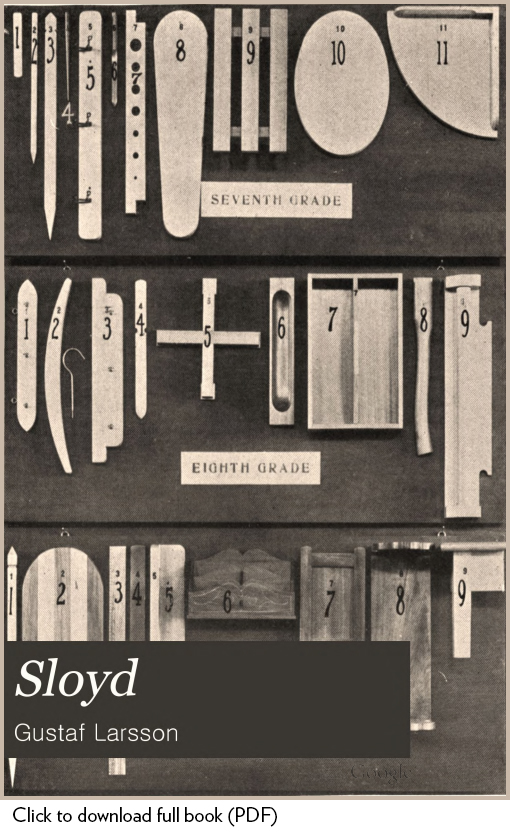

The Sloyd system adopted by North Bennet Street School in the 1890s had the effect of shifting the reliance on the apprentice system for the teaching of traditional trades to a structured program in which tool processes, sequences and construction methods were analyzed and arranged in pedagogical order. A series of woodworking projects was developed in increasing order of complexity, with the result of each a useful household object. With the gradual introduction of new tools, new shapes and new hand skills, each successive project was intended to “secure the constant and proportionate development of mind and body” such that “each should prepare for the next, not only physically but mentally,” according to Sloyd founder Otto Salomon.

Central to this effort was the conviction that hand skills training was not only a path to employment, but of value to the individual for its own sake. North Bennet Street School teacher Lizzie Woodward wrote in 1893 that “books alone cannot restore that balance of mind and body from which purity of thought and life is derived.”

In the Atlantic Monthly in 1899, Harvard Professor William James echoed that sentiment, writing that the value of manual training schools was “not because they will give us a people more handy and practical for domestic life and better skilled in trades, but because they will give us citizens with an entirely different moral fibre.” He argued that hand skills “confer precision, because if you are doing a thing, you do it definitely right or definitely wrong. They give honesty, for when you express yourself by making things, and not by using words, it becomes impossible to dissimulate your vagueness or ignorance by ambiguity.”

Sloyd’s focus on the overall education of the child, rather than the preparation of individuals for the labor force fit well with the philosophy of Mrs. Shaw, who described the school’s mission as training the “whole person”; not teaching “how to make a living, but how to live.”

The need for manual arts training had first gained national attention at the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition of 1876. American educators were enthralled by what became known as the Russian System of Industrial Arts. Victor Della Vos, director of the Moscow Imperial Technical School exhibited a “system” of industrial training that was supposed to move people rapidly from farm labor into jobs in industry.

Sloyd was a rival system of training developed in Sweden, where it was felt that the general skill level of the population was declining due to the availability of ready-made objects. It was developed as a philosophy of general education aimed at improving the mental, physical, and moral development of children, with woodworking as its core.

Unlike the Russian system, in which students were introduced to craft skills after the basics of reading and writing were covered in school, Sloyd was introduced at the elementary school level where it was observed that the development of hand skills and mental capacity were concurrent and mutually reinforcing. While the Russian system relied on classroom instruction, Sloyd stressed bench work and the individual’s development, as opposed to a group’s progress.

Sloyd’s focus on the overall education of the child, rather than the preparation of individuals for the labor force fit well with the philosophy of Mrs. Shaw, who described the school’s mission as training the “whole person”; not teaching “how to make a living, but how to live.”

Pauline Agassiz Shaw sent an exhibition of the School’s Sloyd woodworking program to the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago, and funded the publication of a series of books on Sloyd, including Sloyd As Adapted In Boston (1893) and American Sloyd (1900), as well as a quarterly newsletter The Sloyd Record.

By 1903, Larsson estimated that 34,000 students had been taught by the hundreds of teachers that were trained in the program at NBSS. Sloyd teacher training continued until 1909 when the North Bennet Street location ran out of space and Mrs. Shaw raised money to build a new Sloyd School near the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston.

A century later the shop programs in America’s public schools, which got their start through the Sloyd teacher training program at North Bennet Street School, have been largely dismantled, considered outmoded and unresponsive to the needs of society today.

Pauline Agassiz Shaw’s vision of the value of North Bennet Street Industrial School for educating the “whole person” at first glance may seem outdated for a school with mature students, many of whom have families and a college education. But the concerns of Sweden in the 1870’s still resonate. Otto Salomon developed Sloyd in response to a society he saw as being overwhelmed by inexpensive, ready made, disposable objects and rapidly losing the knowledge embodied in hand-made objects.

North Bennet Street School, the school that once turned away from the Russian System because it “merely” prepared students for employment, now stands apart from most other crafts schools in the country expressly because of its commitment to careers that employ the intelligence of the hands to produce objects that last.

Over 100 years later, promoting the value of hand skills and craft training is still central to the School’s mission, and Sloyd remains the philosophical foundation of our full-time programs in traditional craft and trades.

This article is part of our Founder’s Day series. Learn more about the origins of North Bennet Street School through these great stories:

- A Short History of Pauline Agassiz Shaw

- Sloyd: Training the Whole Person

- NBSIS: Growth and Experimentation

- NBSS: A New Era, Rooted in History