Inside Instruments of the Masters

Categories

Violin Making & Repair

Experts agree that violin making reached its highest potential in 17th-century Cremona, Italy. Great luthiers of the era thrived, such as Andrea Amati, Giuseppe Guarneri del Gesù, and Antonio Stradivari— the maker of the most revered stringed instruments in history.

“There were a hundred-plus years of making and perfecting violins,” says Roman Barnas, Violin Making & Repair (VM) Department Head. “But the masters did not leave a good manual, notes, or a book on how to make them,” he says.

After these masters died, the only way to make a new violin was to look at one of theirs. “People were copying those instruments by measuring and tracing,” he says, “which got more and more complicated over time.”

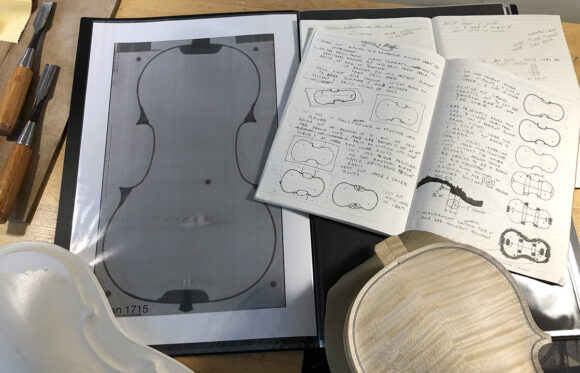

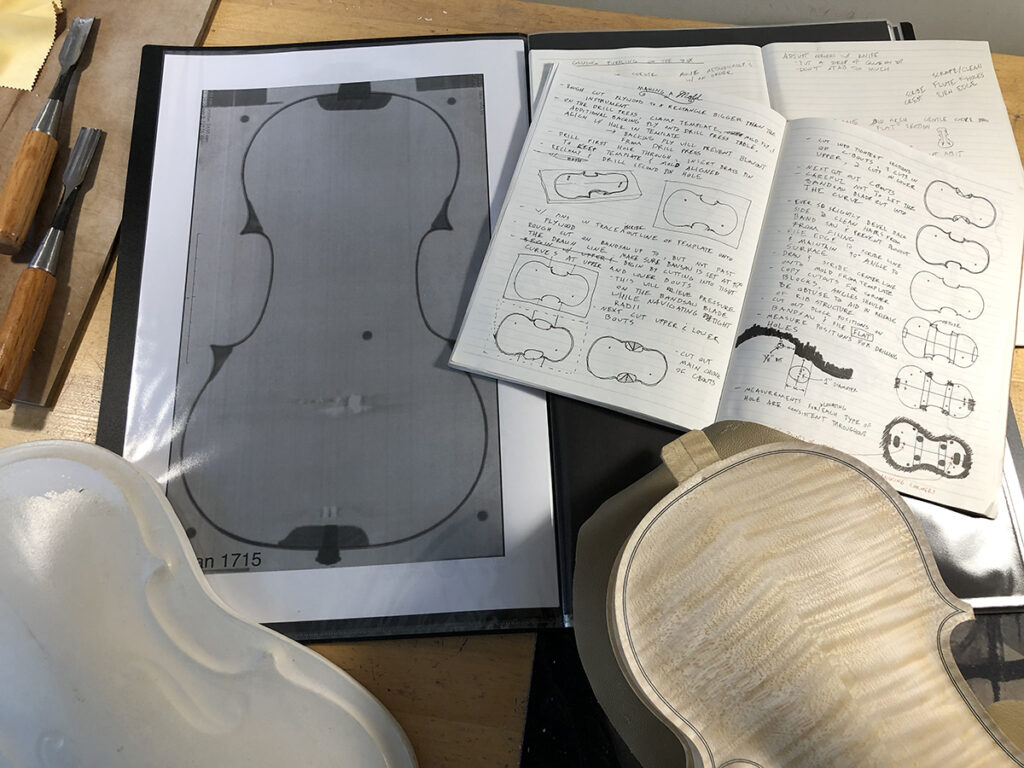

Artisans are still looking to those Italian-made instruments, but the technology has advanced. Although modern luthiers certainly use traditional methods to examine a violin — measuring, tracing, following patterns, looking at photographs, and using moulds — computed tomography (CT scans) allows a detailed look inside without having to take it apart.

Using CT scans is a method Steven Sirr, MD, a radiologist and violinist from Minnesota, pioneered in 1987. He started by putting his own violin in his hospital’s CT scanner and then took the images to a nearby violin maker John Waddle, who was amazed at how much information it showed. “There’s nothing that can hide from a CT scan,” says Steven, who with Waddle has borrowed and scanned many violins over the years, including 32 by Stradivari.

When Roman met Steven during a violin making workshop at Oberlin College in Ohio a few years ago, he was fascinated by the work, and the two became friends. Roman now uses CT scans for instruction at NBSS.

Roman points out that unnecessary stress on an old instrument should be avoided, but a CT scan is noninvasive and provides three great insights. First, it shows the instrument’s “internal air volume, the precise shapes of the arches, and the wood density. All things that aren’t easy to measure with traditional methods,” he says.

Second, it provides a close look at the instrument’s condition, including any damage or components that might not be original. Third, and most important for future generations, it creates a digital profile of the instrument that can be easily shared.

“As a school, we have often questioned how to study violin parts,” says Roman. “With CT scanning, we can understand how the old violins are made and make a good copy, provide a condition report, and preserve the image for the future.”

This information is very helpful in training future luthiers at NBSS. Students use a computer program called Strad3D (created by violin maker and NBSS guest examiner Sam Zygmuntowicz), which compiles information from CT scans into an easy-to-use format with videos that provide a digital look at a violin from the inside out.

Nathan Abbe VM ’20, a third-year student, compares traditional methods with this technology to standing on the outside of the building and looking at it versus actually going inside. “If you’re new to violin making, one of the hardest things is to develop an eye for the shape, because sometimes details are so subtle,” he says. The CT scans “help you understand the differences between the better makers — the small features that make a great violin so special.” Nathan is currently using this knowledge to work on a project inspired by the shape of Stradivari’s 1715 “Titan,” an iconic instrument in the field.

It’s an exciting time for violin making, and to put it all into perspective, when asked when was the best time to make a violin, Roman jokes, “Be an apprentice for Stradivari. But the second best time is now,” he continues, “because we have more information than ever before about the craft.”

This article is from our 2019 Annual Report. See all the stories here, or view more issues.