Making Something That Lasts

Categories

BostonFor 140 years, through every challenge, North Bennet Street School has adapted and endured.

In March 2020, NBSS, along with nearly every other place of learning, closed its doors to ensure the health and safety of its community in light of Covid-19.

The new reality came with alarming abruptness but the School’s faculty, staff, and students reacted with speed and aplomb. Instructors set up regular remote engagement opportunities for full-time students as well as young people in the School’s middle-school programs. Staff dropped off equipment at students’ homes and wired an instructor’s house for high-speed internet.

Meanwhile, NBSS leaders began planning for a safe return in the fall, an adjustment made easier thanks to the School’s up-to-date facilities, with its high-powered HVAC system, wide corridors, and dedicated program areas. (The move to a new building in 2013 seems more fortuitous than ever now.)

It was a testament to the NBSS community’s ability to adapt, to experiment, and to persevere—and indeed, this was just the most recent moment in a long history of nimbleness for an institution that began as a collection of neighborhood social services in Boston’s North End 140 years ago.

“The School leaders before me had to navigate two World Wars, a Depression, the Molasses Flood, the Boston Marathon bombing,” said President Sarah Turner. “Like us, they were mere mortals, not especially trained to adapt to a worldwide crisis in any way, and yet they endured. We drew strength and determination from this history. The School will weather these times too.”

As President Emeritus Miguel Gómez-Ibáñez CF ’99 wrote in his foreword to Rewarding Work: A History of Boston’s North Bennet Street School, by Christine Compston, Stephen Senge, and Walter McDonald: “I can now appreciate both the unchanged nature of the skills that are taught and the dramatic changes that have taken place in the School…. Each of the transformations that [NBSS] has embraced required a commitment of time and money, a vision for the future, and the confidence to venture beyond what is known.”

Join us to take a look back.

| 1880s

North Bennet Street Industrial School (NBSIS) is founded to provide immigrants the skills needed for gainful employment; a disastrous fire nearly destroys the school, but NBSIS rebuilds. |

1890s

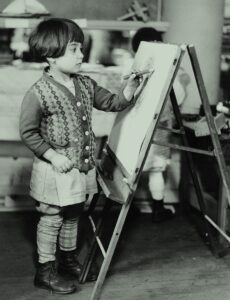

NBSIS adopts the Sloyd system of instruction, and develops manual arts classes for children, in response to neighborhood youth not attending school. |

1900s

Sloyd school for teacher training outgrows its space, moves off-site. New NBSIS offerings include after-work programs, a savings society, and animal rescue league. |

A Community’s Bridge

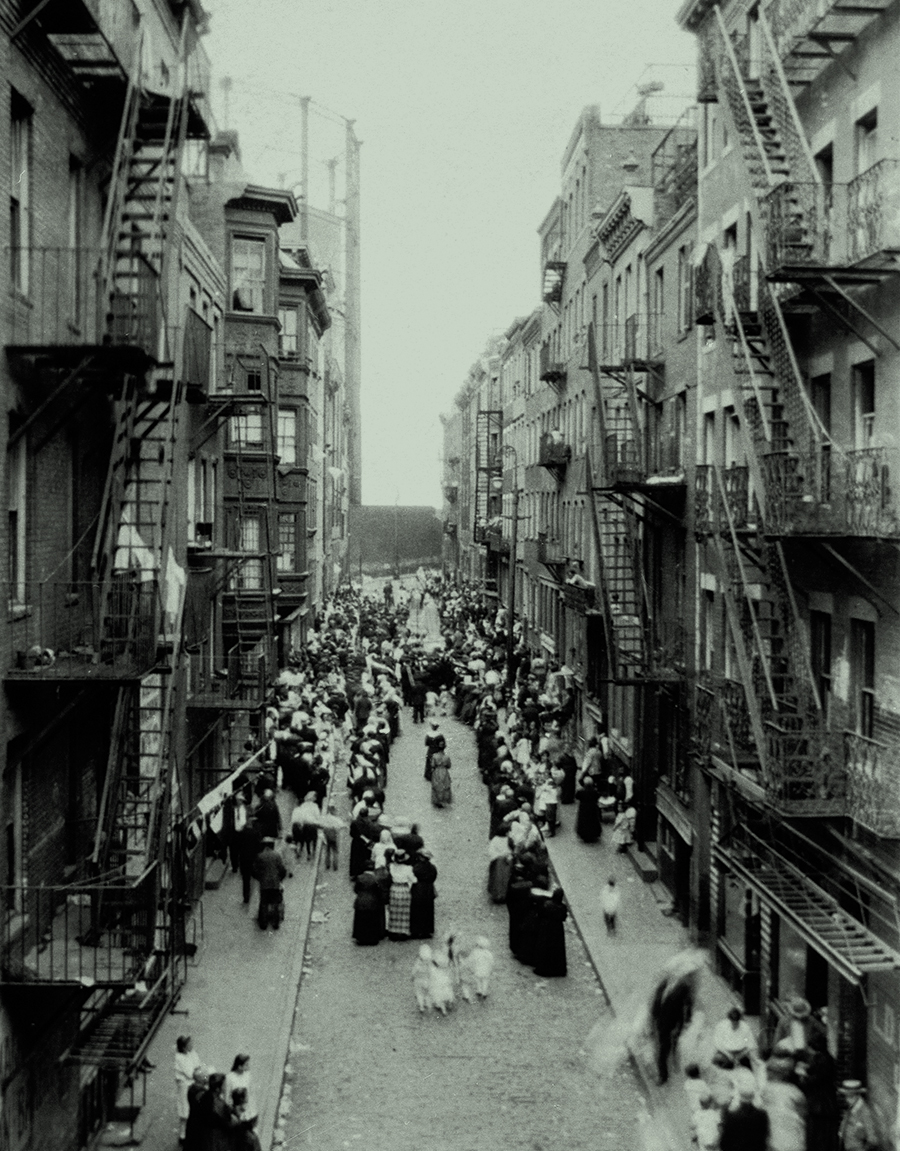

In a way, the very birth of NBSS was a result of global vicissitudes. When the potato crop in Ireland failed in the 1840s, thousands of famine refugees landed in Boston and settled in the North End, close to the waterfront.

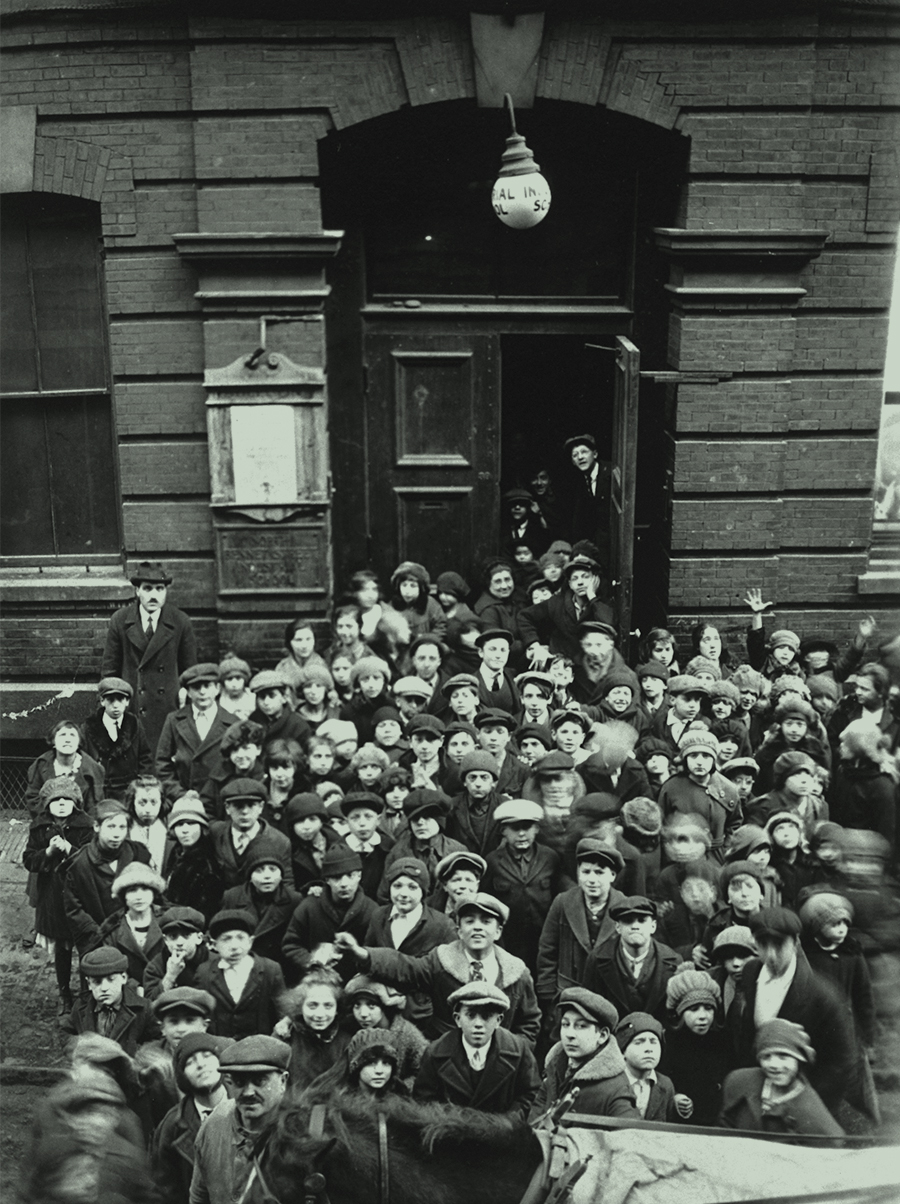

That pattern of migration continued, and the neighborhood’s population ballooned from less than 7,000 in 1840 to 26,000 by 1880, the eve of the School’s founding. (Still predominantly Irish at that point, the North End would soon absorb waves of Jewish and Italian immigrants, reaching a population of 40,000 by 1920.)

The teeming tenements struggled with poverty, disease, and a paucity of jobs. Children ran through the streets, with no place else to go. Worried about the situation, visionary educator, philanthropist, and social reformer Pauline Agassiz Shaw took action. Together with like-minded colleagues, she founded and funded a series of neighborhood programs such as kindergartens and vocational training, including carpentry, printing, sewing, and cooking—open to all but primarily aimed at children, teenagers, and young adults.

These programs coalesced at 39 North Bennet Street in 1881, officially becoming the North Bennet Street Industrial School (NBSIS) in 1885. Besides classes, NBSIS would continue to offer programs such as dances, concerts, lectures, and sports for many decades, but the trades training would prove to be its most enduring and widely known offerings.

The idea was to provide a “bridge, not a chute.” Akin to the adage about teaching a man to fish, practical philanthropists like Pauline believed the way to combat poverty was to erect a metaphorical pedestrian bridge that would allow people to get somewhere, rather than simply dump money down a metaphorical coal chute to be burned away.

Some of the School’s physical assets quite literally burned away in 1886 when a faulty stove in its teaching kitchen sparked a fire on the upper floors, causing at least $9,700 in damages (close to $280,000 in today’s dollars). Undaunted, Pauline and supporters took the disaster as an opportunity to improve the building’s interior layout, making it better suited to the industrial school it was than to the church it had once been.

Two years later, Pauline met Gustaf Larsson, a student of Otto Salomon, pioneer of the Swedish Sloyd system of teaching hand crafts. That meeting was pivotal.

Otto’s work was itself a response to cultural and economic shifts in his native Sweden. It used to be that every winter Swedish farmers would teach their children how to make farm and household tools by hand. But with the new temptations of cheap, factory-made goods flooding the market, that old tradition was dying in the 1870s. Meanwhile, the quality of these ready-made products was poor, leading to dissatisfaction—for consumers and workers alike. With his uncle, Augustus Abrahamson, Otto established an industrial school in Stockholm to preserve the old hand crafts, such as carpentry and metal work.

In their meetings, Gustaf convinced Pauline that the Sloyd approach, with its focus on creativity as well as precision, would work for the NBSIS, developing skills of the head, heart, and hands, and teaching people not only how to make a living, but how to live. As the authors of Rewarding Work write, the Sloyd system would become integral to the School’s abiding commitment to training students for “careers that employ the intelligence of the hands to produce objects that last.”

The School would go on to create a Sloyd program all its own, educating dozens of teachers in the philosophy and finer points of the systems. These pioneers went on to incubate and nurture the Sloyd ethos in schools near and far, a legacy that still resonates today.

| 1910s

Visionary founder Pauline Agassiz Shaw dies, and the great Molasses Flood, WWI, and the 1918-19 flu pandemic all occur. |

1920s

NBSIS supports immigrants with classes in English language, naturalization, civics; Summer youth camps grow in size; New programs for veterans include Watch Repair, House Framing, and Printing. |

1930s

The School establishes a Credit Union and Work Relief Program, addressing both local needs and broader issues in society. |

A Founder’s Death and Social Unrest

A Founder’s Death and Social Unrest

NBSIS was a thriving neighbor-hood institution, reaching an astonishing 2,000 residents per week through its classes and other programming, when Pauline died in 1917. Her memorial service was held in Faneuil Hall, and the hundreds of mourners included the Governor of the Commonwealth.

The death of its founder and chief backer was “the School’s biggest test to date,” wrote Compston et al. After the solemnities were observed, NBSIS faced a budget deficit as well as the loss of a leading light. The School’s new president, Henry L. Shattuck, and director, George C. Greener, navigated delicate negotiations with the Shaw family and scrambled for emergency funding. They succeeded in putting the School on firm financial footing, and even added programming in the coming years.

That was a good thing, because those years were to be turbulent ones for the North End. In 1919, a tank burst at the Purity Distilling Company on Commercial Street. Two million gallons of molasses flooded the neighborhood, killing 21 and injuring 150, leveling buildings, and warping the track supports of the adjacent elevated railway.

Residents had complained about the tank leaking for years, to no avail. The disaster convinced many North Enders of the importance of stronger civic engagement, and it was in the auditorium of NBSIS that they gathered to discuss how to exercise local control over waterfront industrial sites.

The following year brought the notorious collapse of Charles Ponzi’s pyramid investment scheme. Ponzi’s scam had ensnared two of the School’s administrators, and also pointed out the lack of credible financial institutions in the neighborhood. NBSIS responded by launching the Social Service Credit Union in 1921. The credit union was one of many services the School originated and spun off over the decades. Like NBSIS dances and sports programs, the credit union reflects a consistent legacy of the School, to respond quickly and directly to community needs at any given time.

| 1940s

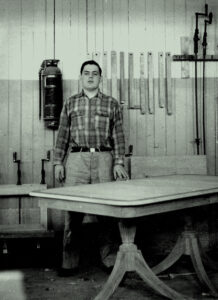

Veterans returning from WWII enroll in NBSIS on the GI Bill®, providing them with civilian careers that leverage their skills. Training programs expand to Cabinet & Furniture Making, Jewelry Making & Engraving, Carpentry, and Piano Technology. |

1950s

The elevated Central Artery effectively cuts off the North End from the rest of Boston. |

1960s

The School continues to support the local community and experiments with with offerings for restless North End youth, including after-school programs, sport activities, and recreational classes. |

Hard Times and a Boom

Hard Times and a Boom

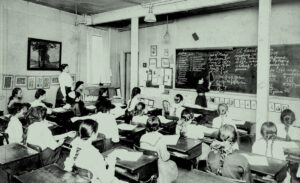

After the stock market crash of 1929, the nation’s economy plummeted. Unemployment in Boston’s North End reached 40 percent. NBSIS leapt into action with revamped manual training classes, a new work placement project, and enhanced social services throughout the 1930s.

Day and night, students packed the School’s trade classes, which now included accounting and bookkeeping, power machine operation, house painting, and cabinet making, among others. Reflecting this state of emergency, NBSIS offered free tuition to the unemployed while staff worked at salaries that were reduced by up to 25 percent.

Moreover, George Greener coordinated a Work Relief program. The School collected donations from wealthy patrons, sought out unemployed skilled and unskilled workers, and matched them with work opportunities. These short-term engagements were with nonprofit organizations in Boston who had small construction and renovation needs that they couldn’t afford to take care of otherwise.

The program kept local carpenters, painters, masons, plasterers, plumbers, glazers, and others busy—between 10,000 and 25,000 days of work—earning between $1.50 and $4 per day ($23–$62 in today’s dollars). The program would find echoes in the 21st century, as the School’s “Jobs & Commissions Board” continues to connect building and repair projects to the students and graduates with the skills to fulfill them.

The Depression ended only when a new global threat emerged, as the U.S. entered the Second World War. At the onset, NBSIS responded by tailoring its power machine training for factory workers making uniforms. The School also added a trade course in blueprint reading and mechanical drawing for military construction, Red Cross first aid instruction, and training for Women’s Defense Corps air raid wardens. (Though less formalized, this spirit of response is echoed in the present day, with the NBSS community eager to contribute their skills to the current crisis. Faculty and staff gave our stores of personal protective equipment to medical personnel and numerous alumni donated their time and work to relief efforts.)

But it was after the war that the School engaged in its most robust efforts to support the troops. Veterans returning Stateside were considering lifelong careers, and the GI Bill® provided funds for college or vocational training. NBSIS worked with the Veterans Administration to add full-time trade classes in sheet metal fabricating and piano tuning and repair. Veterans also enrolled in the School’s courses in Carpentry, Cabinet & Furniture Making, Jewelry Making & Engraving, and Watch Repair.

As word of the School spread, hundreds of veterans enrolled in NBSIS classes throughout the late 1940s, traveling from all over the region by train and trolley to nearby North Station. These events signaled a wider scope for the School, as its reputation and community expanded beyond its North End neighborhood. In that way, the School extended a career pathway for veteran students that continues to this day.

| 1970s

Continuing its focus on career education, NBSIS transfers some social services to other entities, and launches new programs in Locksmithing and Advanced Piano Technology. |

1980s

The School removes “industrial” from its name, and becomes accredited. New craft-focused programs in Bookbinding, Preservation Carpentry, and Violin Making & Repair begin. |

1990s

NBSS launches its short-term Workshop courses (now Continuing Education) to meet the need for short-term skill-building for professionals and hobbyists. |

A Century and More

Those trends continued in the decades after WWII. By the mid-1980s, the School had spun off its social services into a separate organization, the North End Union, in order to hone its focus. The institution concurrently dropped “Industrial” from its name, becoming North Bennet Street School (NBSS) in 1981.

The following year, NBSS earned accreditation from the National Association of Trade and Technical Schools, as well as designation as a postsecondary institution from the U.S. Department of Education.

Courses were added in Violin Making & Repair, Bookbinding, and Preservation Carpentry, bringing the total number of programs to nine altogether. The School came to look much as it does today, albeit bursting at the seams in its original, ad hoc space on North Bennet Street.

Under the leadership of Miguel Gómez-Ibáñez CF ’99, the School made its historic move to North Street in 2013, occupying the 65,000-square-foot space previously housing the City of Boston’s printing plant and a police station. The purchase and renovation of the new facility was made possible by the School’s Under One Roof campaign, in which more than 200 donors contributed $17.05 million.

The new space has been a godsend in 2020, as the School has responded to this latest challenge. “I think I’ve never been so grateful for a new HVAC system as I was this summer, while planning our reopening,” said Turner. “To have an HVAC system that’s young, that can handle the proper filters, to have the capacity to operate a terrific dust collection system, to have windows that open and close, hands-free hand-washing stations—I’m just very grateful for our longstanding community support and the good physical plant planning.”

President Sarah Turner has appreciated the influence of the military veterans who still comprise a large segment of the student body—up to 20 percent in some years—when it comes to following new safety protocols, she said. “They’re often team-oriented, understand safety, careful discipline and the need to put the greater needs first.” Besides which, Sarah added, NBSS’ safety culture is of long standing. “Asking students to wear a mask, wash their hands, self-attest—these are just additional protocols on top of the safety steps they already take every day.”

One of the most critical, and heartening, ways that the School pulled through the early months of the Covid-19 crisis, was the outpouring of support via the NBSS Emergency Fund. Those unrestricted donations allowed the School to address its most urgent needs—tuition relief, support for faculty, and the new technology and training that made remote engagement possible.

“We were financially healthy before this, and part of that is prudence on the part of the School, and part of it is our strong network that has developed over many, many years,” said Turner. “We were able to weather this crisis because we could rely on a community.”

| 2000s

With completion of the Big Dig, the Rose Kennedy Greenway is created, re-connecting the North End to Downtown Boston. The School experiences substantial growth in its programs, requiring satellite locations for three programs. The search for a new home begins. |

2010s

A successful $15M fundraising campaign helps brings all of NBSS programs under one roof, and the School moves locations, just blocks away from the School’s original site. |

2020

The School closes its facility temporarily in light of the Covid-19 pandemic, moving to remote instruction and operations. NBSS supports front line workers with PPE donations, and its students with an Emergency Fund. The School re-opens with new protocols and new uses of technology, continuing its legacy of addressing and adapting to challenges. |

The NBSS community looks forward to 2021, when the School will celebrate its 140th anniversary. Though faced with many uncertainties in the world, NBSS has proven its ability to adapt and respond to challenges time and time again.

That self same spirit of ingenuity, grit, and determination continues, and, with the strength of history and community at its back, the School is well-positioned to lead and to grow to the next century, and beyond.

For more School history, visit nbss.edu/history.

This article is from our 2020 Annual Report. Read more stories from the issue or view more issues.

Historic images courtesy Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University

A Founder’s Death and Social Unrest

A Founder’s Death and Social Unrest

Hard Times and a Boom

Hard Times and a Boom